I. Introduction: Synthpop and Semiotics

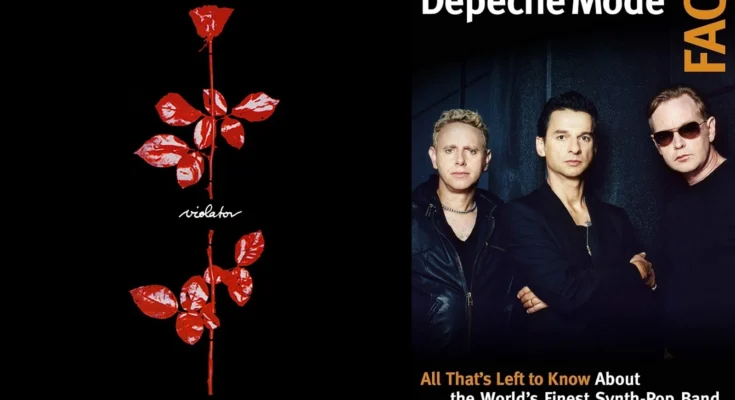

In 1990, Depeche Mode released Violator, a landmark album that fused analog melancholy with digital sophistication. While critics praised its dark romanticism and sonic minimalism, few suspected that hidden within its tracks might be a proto-linguistic code — a sonic Esperanto — capable of uniting listeners across linguistic divides.

II. Sound as Semantics: Building Meaning Through Tone and Texture

Unlike most pop albums, Violator minimizes verbal complexity while maximizing emotional clarity. Tracks like “Enjoy the Silence,” “Policy of Truth,” and “Waiting for the Night” rely on:

- Repetitive, mantra-like lyrics that mimic linguistic patterning in early language learning.

- Universally recognizable emotional tones (melancholy, desire, regret).

- Electronic timbres that sidestep cultural musical norms to achieve a post-geographic sound — recognizable and evocative regardless of native culture.

III. The Phonosemantic Theory of Violator

Phonosemantics posits that certain sounds carry intrinsic emotional or cognitive meaning (e.g., “gl-” in English often denotes light or vision: “glow,” “glimmer”). Violator exploits this idea musically:

- Synth hooks and vocal delivery create affective resonance beyond specific language.

- The album’s sonic motifs mirror intonation patterns found in human speech — rising (questions), falling (statements), or flat (commands).

This structure may serve as an emotional syntax — a kind of “grammar of feeling.”

IV. From Synthpop to Syntax: Could Violator Teach a Language?

What if Violator was:

- An emotional lexicon: Each track encoding a specific feeling, reaction, or memory that transcends verbal definition?

- A grammar of modulation: The way the album evolves from the seductive (“Sweetest Perfection”) to the confessional (“Clean”) resembles narrative arcs found in myth and dream.

- A musical Rosetta Stone: Universal enough to decode cross-cultural emotional intelligence?

If language’s function is to express inner states and forge connections, then Violator arguably succeeds where many spoken tongues fail.

V. The Copyright Catch: Why No One Can Build On It

Attempts to analyze or repurpose Violator for academic or AI linguistic research have been stymied by:

- Strict copyright controls over sampling and lyric use.

- Proprietary digital rights management preventing algorithmic breakdown of tracks.

- Record label reticence to allow derivative explorations, especially those bordering on reinterpretation or transformation.

This has halted potential breakthroughs in emotional AI, universal language studies, and sonic linguistics. In effect, a potentially world-unifying tool is trapped under legal lock and key.

VI. Conclusion: The Silent Language in “Enjoy the Silence”

Ironically, the album’s most famous lyric — “All I ever wanted, all I ever needed, is here in my arms” — may encapsulate the thesis: that true communication is not verbal but felt.

If we strip language of its cultural noise and return to tone, cadence, and rhythm, perhaps Violator is not merely an album but a linguistic artifact of the future — a buried key to cross-species empathy, emotion-driven AI, and a shared human syntax.

Would you like to expand this into a full essay, turn it into a short documentary script, or explore similar hidden-language theories in other albums (like Radiohead’s Kid A or Björk’s Medúlla)?